Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

During the 1990s, a few years before my father, Dave, passed away in December of 2000, he wrote a 35-page autobiography. Excerpts from it will be published here, as companions to the diaries my mother, Dorothy, kept in 1945 and 1946—the year she met Dave. My dad was born in 1927, in Hamilton, Ohio. The family eventually moved to the south side of Chicago.

Part 3

Getting By

My memories of our time in the house at 53rd & Peoria Streets are much clearer than those of Hamilton, Ohio.

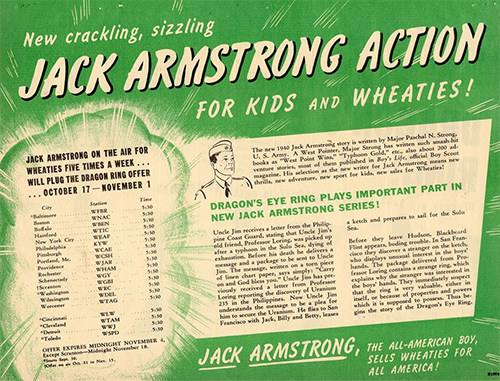

Sitting alongside our big, floor model radio, I would listen to Jack Armstrong: All American Boy, and Little Orphan Annie. On top of the radio was a lamp. It had a base that resembled rocky hills, on which I put kitchen matches, pretending the matches were cowboys and Indians. In the evening, we'd play “It,” and “Kick the Can” on the street by the lamppost. Mom would call us in—a number of times. We wouldn't pay much attention. That is, until we began to hear her voice take an angry turn.

My older brother was always telling me “Shut off the radio and go read a book!” Or, “At the very least, listen to some classical music!” He wasn't nice to me, I thought, at the time, and it made me afraid of him. But since he had a car, he'd often be out someplace.

Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy

Sara, my older sister, has a job. She'd send me to the store for ten cents worth of lunch meat, so that she could take a sandwich to work. My other sister, Ruth, has gone to live with Uncle Charlie and Aunt Mame.

My brother Charlie and I spent lots of time together. Charlie helped out at a newstand under the “L” tracks, at Root & Halsted Streets. He'd take me with, and then I'd get to hand out the newspapers and collect the money. Charlie would deliver papers to nearby offices. We sold the evening editions of the Herald American, Chicago Daily News, and Abbenpost–a paper that was read by the German Stock Yards workers.

Across the street from the newsstand was a lunch counter that had been made from an old railroad car. Charlie and I would offer to clean the floors and the back room, in exchange for a meal.

Charlie and I would, out of economic necessity, would manage to find breakfast out on the streets. Back in those days, things like milk, cheese, and cream were delivered in the early morning by horse and wagon, and left near the front entrances of houses and apartment buildings. Likewise, bread and sweet rolls were placed near the front doors of the grocery stores an hour or two before the shops opened up.

Food was cheap then, but money in our household was scarce. Mom would send me to the A&P at 53rd & Halsted with about fifty cents, and I'd return carrying a big bag of groceries. With mom's money, I'd buy large loaves of day-old bread for three cents, and hamburger for fifteen cents per lb. Jack Doyle, the A&P manager, knew my dad, and would set aside the dented or unlabeled cans, broken packages, and other items, just for us.

Our family was on “relief,” as government assistance was known at the time. Twice a month, on Saturdays, I'd go with Mom to visit the “relief station” on 55th St., me pulling a coaster wagon. I would feel so ashamed on the way home, pulling a wagon full of food that was clearly labeled “Relief Products.” I just knew that everyone was looking at us, and knew how poor we were. Our family was on “relief,” as government assistance was known at the time. Twice a month, on Saturdays, I'd go with Mom to visit the “relief station” on 55th St., me pulling a coaster wagon. I would feel so ashamed on the way home, pulling a wagon full of food that was clearly labeled “Relief Products.” I just knew that everyone was looking at us, and knew how poor we were.

At Thanksgiving and Christmas, we were given baskets of food, on the condition we kept a photo of Mayor Kelly [pictured] in our front window.

Chicago's streetcars charged seven cents for adults, three cents for us kids under the age of 12. Most often we would sneak aboard when the cars were crowded, or by convincing the conductor that we had lost our transfer tickets. The window next to the motorman up in front was the best place, because you could pretend to the driver. Sometimes, we'd be allowed to ring the streetcar's bell by stamping on the plunger by the motorman's foot.

We'd gaze out the streetcar windows at all the strange neighborhoods. Little Italy, along Taylor St., with its baskets of macaroni shells outside little shops. Crowds of people walking amongst the stands and stalls in the Jewish part of town, along Maxwell St. The “bums” on Madison. The Poles just north of Division.

Charlie and I would ride all the way to the south end of the line, at 111th Street, or all the way north, to Halsted & Broadway, when the conductor would then flip the seats to face the other direction. Once in a while we'd be told to get off, but we didn't care. If we had no money to ride again, we would bum pennies or transfers, or tell a different conductor a story.

All these things we did as a matter of course. No plans. Just getting by.

* * *

End of Part 3

Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

|