Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

During the 1990s, a few years before my father, Dave, passed away in December of 2000, he wrote a 35-page autobiography. Excerpts from it will be published here, as companions to the diaries my mother, Dorothy, kept in 1945 and 1946—the year she met Dave. My dad was born in 1927, in Hamilton, Ohio. The family eventually moved to the south side of Chicago.

Part 6

Leaving Home

One night back in 1938, my brother Charlie and I were sleeping, up in the attic, when we suddenly I heard my mother scream. We didn't know what was happening until we saw her the next morning–smiling as she held our new baby sister, Delores. Times were tough though.

I'd gotten a job milking cows for a neighbor, after school, for which I was given a pair of bib overalls, and paid 50 cents per week. One of our own cows had recently died. A man named Bill came by to take it away, the smell of dead animals permeating his truck.

Bill began to visit us quite frequently, often taking my sister Ruth and me along with him to the “free show”–the outdoor movies–or into town for ice cream. Eventually, Ruth confided to me that she'd be eloping with Bill, but that she would not be telling mom or anyone else. She trusted me to keep their marriage a secret.

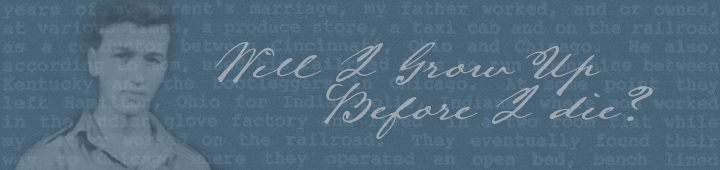

Charlie, my brother, left home, too, to join the C.C.C.–the Civilian Conservation Corp–and it would be three years before I saw him again, or even heard from him. He never wrote to us. Consequently, I am now the oldest, and there were a lot of chores for me to do. As soon as I got home from school, I'd have to go out in the field and retrieve the cows, feed and milk them, and clean the barn. There was wood to be split for the stove; all the chips and kindling.

Plaque at Indiana's Spring Mill State Park, commemorating President Roosevelt's Civilian Conservation Corp

Our farm land was not in good condition. Most was either wooded or sandy. Our crops never did well, and were never enough to support us. Clark, my step-dad, often hired out to the neighboring farmers for one dollar a day. On occasion, we were able to trade chicken eggs and produce with the Winamac stores, for other foodstuffs and clothing. A good many of our meals were simply biscuits and milk for breakfast, and biscuits with milk and gravy for lunch and dinner. Beans, cornbread, and salt pork were other staples of our diet.

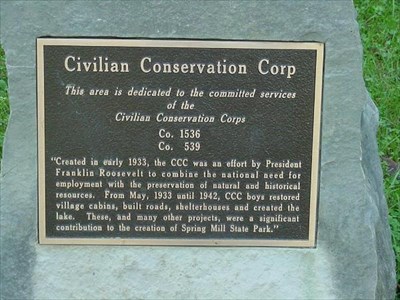

As 1939 ended, Clark began traveling to Chicago to look for work. He'd been told that the Link Belt Company was hiring in anticipation of a possible wartime production need.

A 1939 advertisement for Link-Belt, the Chicago company where Dave's step-dad, Clark, had set out to find employment

Meanwhile, things were bad at home.

It was a hot day when I was working in the corn fields, the stalks taller than me. I was thirsty and hungry. In the house, I dip a glass into our bucket of water. Mom is at the kitchen table, making biscuits (I'd been told we could now eat only twice a day.) As I sat down, Mom looked at me with eyes that, all her life, seemed water-filled. “I want to leave,” I said. Without saying a word, she nods her head. After all these many years, I remember those moments with the clarity of having experienced them only a moment ago.

And so that afternoon, I set out for Winamac, ten miles away, walking, and then hitch-hiking the remaining distance, until I arrive at a little one room cabin, the home of my newly-married sister Ruth and her husband Bill. Although it's hardly large enough for the two of them, they take me in. I'm given a small space, perhaps six feet by twelve, behind their wood-burning stove, and separated from the rest of the cabin by a blanket strung between the walls.

Bill's job with the dead animal pickup service required him to be on-call seven days per week. He would deliver them to a rendering plant 30 miles from Winamac, where he would unload them and then clean the truck. For this he was paid $19 weekly–half of which was paid out as rent for the cabin and the parking fee for the truck. One way he increased his take was to drive with Ruth and me to his brother Ollie's farm.

Bill had figured out a way to “set aside” an animal or two for extra income. Since we were worried about being caught, Ruth and Ollie's wife would keep watch in the kitchen, with instructions to blink the light if anyone drove up. Out in the field, Bill, Ollie and I would skin the animal while I kept on eye out for the flashing kitchen light. Once the carcass was cut up and buried, Ollie would give Bill $5 for the cowhide.

Looking back on all this, I am amazed that we didn't all die of some disease from the livestock we handled.

A lot of what Bill and I did, such as spear fishing on the river without a license, while we watched out for the game warden–was not all that different from the shenanigans Charlie and I had once been doing. Everything was a bit “off center”–illegal, but it was what we had to do to get by. I became so good at setting up traps and lines, and catching fish, that I was able to clean and package them for sale door-to-door in town.

My very first business venture, and it was a success.

* * *

End of Part 6

Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

|