Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

During the 1990s, a few years before my father, Dave, passed away in December of 2000, he wrote a 35-page autobiography. Excerpts from it will be published here, as companions to the diaries my mother, Dorothy, kept in 1945 and 1946—the year she met Dave. My dad was born in 1927, in Hamilton, Ohio. The family eventually moved to the south side of Chicago.

Part 14

The Kachin Hills

As I was boarding the Kaiser-built “Liberty Ship” at Long Beach, California, I thought about how not so long ago I was hopping on and off Chicago streetcars, selling kitchen knife sets door-to-door.

It was early summer of 1944 when we sailed off for Calcutta, India–a place I was only vaguely aware of until now. Twelve of us were quartered in a wooden structure, topside and midship. The 50-day voyage, although very long, was uneventful aside from a brief, three-day liberty in Melbourne, Australia.

By August, we had pulled into port at Calcutta. After being shuttled to an Army Transport Service airfield just outside the city, we were told what we could expect next.

The Arakan group had been formed and trained for missions near Burma's western border. Our job would be to organize local partisans, who would then assist us in raids upon Japanese coastal installations.

While we waited for our equipment and transportation, a call came in. A medically-trained person was needed. The obvious choice was me, since I was the only one with those credits. As a result, and before I knew it, I was driven by jeep to the hanger area, issued a weapon, ammo, K-rations, maps, and a parachute, which I was promptly strapped into. Within one hour, I was aboard a C47 transport plane, headed across the Bay of Bengal. Destination, Burma. I had been in India for just three days.

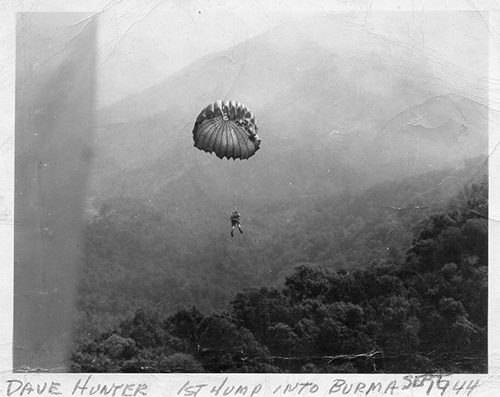

It was four hours into our flight when the light by the open cargo door turned red. The jumpmaster approached me. “How's your static line?” He checked it, and gave me the thumbs-up signal.

Throughout all this, I wasn't frightened. My state of mind was more of a trance—more of an outside observer, and not quite connected to what was happening. This feeling was to stay with me over the months to follow. A sensation that I'm sure many have had when in harm's way, and one which governs the time and their subsequent actions, as it did mine.

The C47 dropped down to about 500 feet. The low altitude would minimize the chances of a parachutist being spotted. The light turned green. I stepped over to the open door, and jumped.

“Dave Hunter - 1st jump into Burma, Sept. 1944”

When I landed, I was on a clearing atop a hillside, overlooking a valley. A larger hill was on the opposite side. Little did I know at the time that upon that hill was a Japanese military encampment. A few minutes passed by as I regained my bearings, when I got the a signal that friendly forces were approaching. It was a group of three: a radio operator, an NCO (sergeant), and Lt. Bill Martin, the group's leader. I joined them as the replacement for their medic, who had been wounded the week prior, and flown out to a field hospital.

We descended the hillside. Following a brief trek, we met up with twenty members of the native Kachins, a Burmese tribe. Small in stature (the tallest of them perhaps 5' 5"), the Kachins were very young, most of them 14 to 16 years of age. Their leader, equal in rank to our sergeant, had once been in the Burmese English Army.

We sat down to discuss our upcoming operations, as the OSS called them. Mainly, they would involve collecting information about the enemy. To do this, we would use whatever methods were appropriate at the time. Ambushes and demolition, in particular. Throughout operations, we would be in daily radio-telegraph contact with our base in northern Assam.

The Kachin Hills

Only a few days following my arrival, we set out on our first mission. The jungles of Burma were a rugged place. Nevertheless, we covered 40 miles in one day and night before reaching our target: a Shan village that was known to harbor Japanese collaborators. (The Shans were another Burmese tribe.) My OSS team set up a block along the trail that led out of the village's center.

The Kachins went in. They returned with three Shans, who then admitted to us that they were scouts for the Japanese, and also that a Japanese garrison had pulled-out of the village just a few days before.

We were as much as 100 miles inside the enemy lines, with no means of extracting ourselves or anyone else except on foot. The thick jungle eliminated any possibility of clearing a landing strip. It was impractical for us to have prisoners with us during our operations.

We tried and convicted the three Shans as spies, given that they admitted to working for the enemy, and wore no uniforms. Along with two of our Kachins, I was given the job of carrying-out the sentence. The three of us were ordered to dig a trench, and then to tie the hands of the kneeling Shans behind their backs.

One of the Kachins spoke to Shans in what I took as an announcement and explanation of the sentence. When, after several minutes, he'd finished talking, the Kachin pointed to my pistol. “Duwa,” he snorted, as he made a shooting gesture towards the back of the prisoners' heads.

I walked over to Lt. Martin. “What am I supposed to do?,” I said.

“Execute them,” was his terse reply.

I turned, and proceeded to carry out the officer's order.

That sense of being outside looking in that I spoke of earlier washed over me. I can honestly say that I did not feel anything at the time of this event. Why not? I don't think I had lived long enough. I hadn't yet had enough life experience yet to know compassion.

Dave jumped into the Kachin Hills area of northern Burma. The OSS base was located to the west, in the Assam section of India.

Altogether, I was part of three more penetrations into enemy territory with Lt. Martin's Arakan team. Our sergeant rotated out and was replaced with a new one. The radio operator was wounded and evacuated. His replacement was none other than Art Logue—my fellow Arakan member, who had joined me on our ill-fated attempt to surf from Catalina to Long Beach, in what now seemed like ages ago.

After that third and final mission, Art and I were granted leave. We caught the train in northern Assam for Darjeeling, in the Himalayas. We'd been there just a couple of days, when we were arrested by British M.P.s “Drunk and disorderly,” was the charge. “Do not come back here,” were their not-so-friendly parting words, as we were unceremoniously placed aboard a train for the journey back to Assam, and a return to the War.

* * *

End of Part 14

Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

|