Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

During the 1990s, a few years before my father, Dave, passed away in December of 2000, he wrote a 35-page autobiography. Excerpts from it will be published here, as companions to the diaries my mother, Dorothy, kept in 1945 and 1946—the year she met Dave. My dad was born in 1927, in Hamilton, Ohio. The family eventually moved to the south side of Chicago.

Part 5

Street Life to Farm Life

In the summer of about 1937 or '38, it was so hot that we would pull bits of tar up from the street, and form it into “marbles.” We made a hole in the dirt and drew a circle around it to mark off the playing area. All the kids in the neighborhood carried marbles–whether real ones or our tar balls. We always had a “shooter” marble, too, the idea being to shoot it at another player's marble, knocking it into the hole. You could keep on shooting and hitting marbles until you missed–a lot like pool. If you did hit one, you got to keep the other player's marble.

Another favorite of ours was “Hearts and Noses,” a card game. The winner got to hit the losers on the sides of their noses with the cards. We played “Lag the Pennies,” which, if you were good (I wasn't) meant that you could keep all the money.

Taken all together, these years were the best of times, a time before people began to talk about pollution, environmental waste and all the other problems we now know we had in abundance then, but didn't know it. A time when each neighborhood had its ethnic group (although we didn't know the word “ethnic”)—groups that were strange, suspect, and generally avoided. We were not aware of racial issues because we all stayed away from each others' patches. We were certainly a prejudiced lot though, always denigrating people of other ethnicities, not conscious of our stupidity.

Our attention was mainly focused on obtaining money, finding food, and figuring out how to pass the time of day. We were children of our time–roaming the streets day and night without fear of gangs or drugs, committing petty theft, doing what we had to do to get by, day to day.

I've always felt that my life has been made up of separate and distinct parts. The first and perhaps the most formative was during 1938 when my mother remarried. Cliff came to live with us during that hot summer.

I hadn't known what was happening except that I would see mom often kissing Cliff, and that he was over a lot. I had no conception of the word “father.” Cliff was simply just another person around the house. My older brother and sister considered him a lesser man than our biological dad, and consequently never bonded with him. In my later years, and upon examining my feelings, I came to the conclusion that mom, being a young widow, above all else needed the companionship he gave her.

After a while, Clark talked my mother into selling our house, and moving to an 80-acre farm near the small town of Winamac, in northwestern Indiana. All our things were hauled there in a big truck. Mom, Clark and the baby, Ann Adele, in the front seat. Ruth, Charlie and I in the back, open part of the truck. We must have looked for all the world like the “Okies” in The Grapes of Wrath. Or worse. My older siblings–Sara and Oregon–stayed behind in Chicago.

“Okies” on the move, in a scene from The Grapes of Wrath

There at our new home, I spaded up a large patch of soil near the house with my shovel, in order to plant a vegetable garden. We had mules and an old tractor that had steel lugs rather than tires. I would take the cows out to the back of the field near the woods and sit with them while they ate their feed. One day, Oregon, my older brother, came to visit us and proceeded to get into a fist fight with Clark, whose son and daughter–Marion** and Adrian–from a previous marriage had been living with us. They eventually departed.

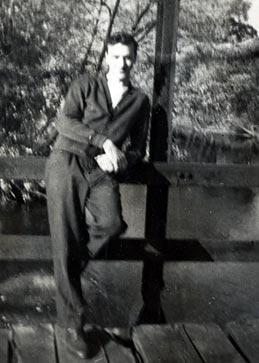

On a Tippecanoe River bridge, about 1946

I learned how to milk the cows, and to plant and pick the corn we grew. We'd go in our truck to nearby Bruce Lake to see the “Free Show,” an outdoor movie, to which people would bring chairs, or sit on the grass.

The Tippecanoe River flowed around the town of Winamac and nearby the farm

School, there in Indiana, meant traveling by bus to the town of Monterey. It was much different than the Catholic schools I attended in Chicago, before they began charging tuition. First at Nativity, where I was confirmed, and later at Visitation Catholic School, when we lived at 53rd & Peoria.

I liked going to church. I recall the beautiful statues, candles and softly-lit alter, and dozing off while I waited for my turn at the confessional. The feel, the sounds, the pageantry. It was like being in a movie or a play. I knew all the prayers and would always put my envelope and its 75 cents sin the basket. We'd cross ourselves when a funeral procession came by, and whenever we walked past a church, or a house where someone had recently passed, that had wreaths with purple ribbons hung on its doors.

Times seemed harder there on the Indiana farm. We had less to eat, and there was always work to do. There were too many people around, all the time. Charlie and I slept in the attic, which had a hole in the floor for heat to come up from the wood stove below. We had a chamber pot under the bed to use during the night, so that we wouldn't have to trudge outdoors to the privy.

The world now seemed smaller.

* * *

End of Part 5

** My dad wrote, incorrectly, that Marion had been killed in WWII. However, Ann, his sister, reports that he eventually moved to Arkansas, got married, and was the father to two children. —David

Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

|